Park Chan Wook’s Decision to Leave is a study in restraint. At a first glance, it is unlike most of the directors’ body of work, dwelling more on the peaceful ordinary than the violence and gore many have come to associate with Park’s cinema. But Decision to Leave emerges as his best directorial endeavour to date – flourishing because of the very thing that sets it apart – the mundane.

Decision to Leave is a story about a detective, Jang Hae Jun, trying to solve the murder of a man who fell to his death from a mountain. He becomes embroiled in a tale of deception and desire with the widow and the main suspect, Song Seo Rae.

Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli is often praised for its use of breaks in the narratives that give its characters and viewers an opportunity to reflect on the circumstances. These scenes focus on ordinary things like washing the dishes, setting the table or enjoying a nice meal. We often find these excluded from most of Western cinema as they don’t necessarily further the plot. But what they do offer is a depth to a character, helping flesh out an alive person with their own habits and eccentricities rather than a few characteristics put together by a writer. This is what Park explores in Decision to Leave.

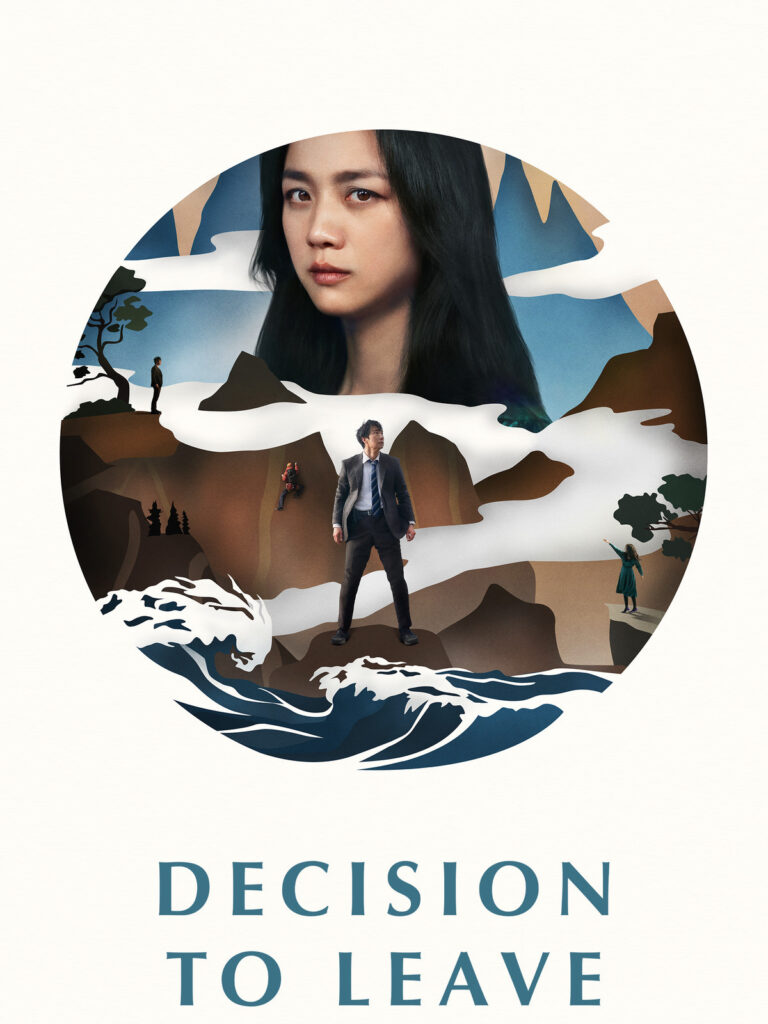

Hae Jun and Seo Rae are the mountain and the sea – a juxtaposition common in South Korea due to the peninsula’s geography. It is a common question one might ask on a first date – what do you prefer, the mountain or the sea? Hae Jun is a sturdy mountain, a man of principle who tries to move through an investigation with procedure and correctness. But he is guilted by the waves of passion that come crashing against him in the form of Seo Rae. He knows he shouldn’t want her, knows that their love could never be true, but he is helpless against the ocean whose rhythmic quietude brings a much needed sense of calm and peace to his life. The mountain and the sea are characterised as polar opposites yet they remain forces of nature – both drawn to one another by the high and low tides of their lives.

In my review of The Handmaiden, I talk about Park’s love for wrapping his story in layers of hidden meaning by using subtext and imagery to his advantage. Decision to Leave is no different; it demands that you pay attention. An investigation scene which might have been boring and serve as nothing more than exposition in another’s hands becomes the best scene of the film in the hands of the maestro. The two leads and their reflections go in and out of focus to convey connection and subconscious desire to the viewer. They switch between Mandarin and Korean, both trying to grapple with their yearning for the other, yet staying separated by their sense of duty and inability to understand each other.

Much like his previous films, Park makes extensive use of symbols and imagery to create a visual poem. The wallpaper of Seo Rae’s apartment keeps you wondering if the pattern is a mountain range or the waves of a stormy sea. Turquoise – a mix of blue and green, of the mountain and the ocean – can be found in every frame. A sushi box alludes to the climax. The film has an undercurrent of desperation and leaves you with a sense of devastation long after it is over.