The theme for the 2025 Met Gala, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” drew inspiration from Monica L. Miller’s seminal book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. On Monday morning in New York, celebrities embraced this celebration of Black elegance and resistance in fashion with varying degrees of depth and flair. Some were expected highlights—like Vogue livestream host Teyana Taylor in a sculptural red-and-black ensemble by Ruth E. Carter, or 2025 co-chair Lewis Hamilton in an ivory suit by Wales Bonner. Others, like Kim Kardashian in a dramatic Chrome Hearts two-piece, took more interpretive approaches. Yet among this sea of tailoring, symbolism, and spectacle, it was Punjabi singer-actor Diljit Dosanjh who emerged as the most compelling and surprisingly on-theme guest. Dressed in an ivory sherwani inspired by the regalia of the Maharaja of Patiala, Dosanjh reimagined the Black dandy’s sartorial strategy through the lens of South Asian colonial resistance and cultural reclamation. How does a Punjabi man in a turban, cape, and ceremonial sword manage to interpret the theme more effectively than those in the sharpest of suits? The answer lies in understanding style as not just tailoring—but storytelling.

Tailored Resistance

Traditionally, a dandy was simply a man who dressed well—think polished shoes, crisp tailoring, and an air of refinement. But within Black culture, dandyism carries a different weight, one shaped as much by intention as aesthetics. While Black men have been part of the dandy tradition from its inception—helping shape its visual codes—it was after the emancipation of enslaved people that Black dandyism took on sharper cultural and political significance. In the segregated America of Jim Crow, dressing with elegance became a radical act: a tool for self-definition, resistance, and visibility.

Its influence surged during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s—a period of profound artistic and intellectual awakening centred in Harlem, New York. Fashion, alongside music, literature, theatre, and politics, became a stage for Black identity and autonomy. In Slaves to Fashion, Monica L. Miller frames Black dandyism as a direct response to the dehumanisation of slavery, writing, “[Africans] arrived in America physically and metaphorically naked, a seeming tabula rasa on which European and new American fashions might be imposed.” Against this backdrop, Black dandyism emerged as a way to reclaim the body, to use clothing as both armour and assertion—of personhood, pride, and power.

After World War II, this aesthetic became inseparable from the image of the Black Power movement, embraced by figures like Malcolm X and Sammy Davis Jr. Today, it continues to evolve through the style legacies of icons like the late André Leon Talley and 2025 Met Gala co-chair Coleman Domingo—reminding us that tailoring, in this context, is never just about the fit. It’s about what the fit means.

Maharajas and Modernities

So what does any of this have to do with the Maharaja of Patiala?

During the same period as the Harlem Renaissance, India was undergoing its own reckoning with white colonialism—a cultural and political awakening that sought to reclaim identity from imperial domination. While Mahatma Gandhi encouraged a return to simplicity through homespun khadi, promoting self-reliance and the boycott of British goods, there was another parallel assertion of Indianness playing out among the princely elite. The maharajas—particularly those from Punjab, like the rulers of Patiala and Kapurthala—asserted their sovereignty and identity not through austerity, but through extravagance. Their language was one of opulence: dress, jewels, and spectacle.

Dressing for the Empire

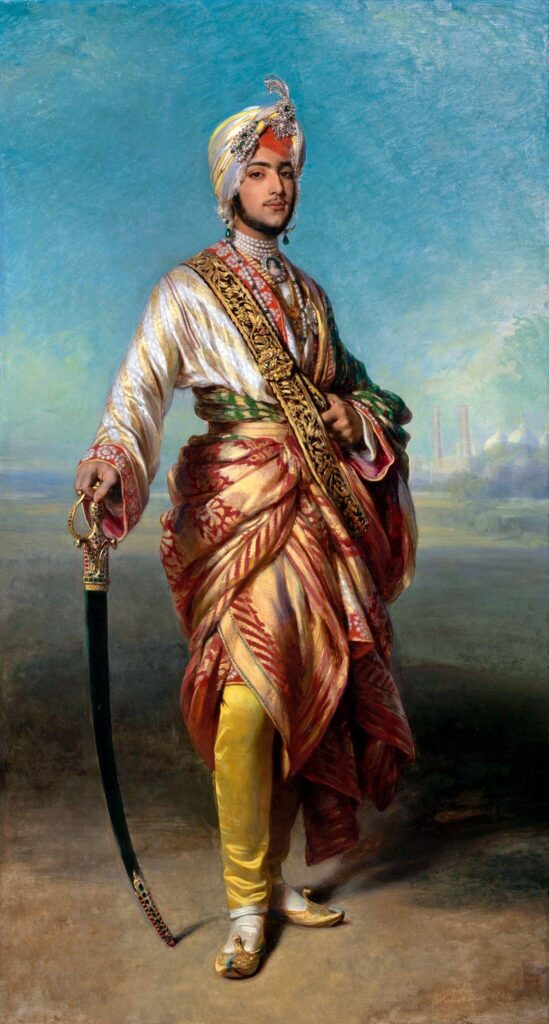

This performative style had deep roots in Punjabi royal history, particularly in the legacy of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire. Though known personally for his asceticism—favouring white sherwanis, churidars, and a matching turban, with little adornment save for the gleaming Kohinoor worn on his arm—Ranjit Singh was immortalised in portraits as richly robed and bejeweled. But it was his son, Maharaja Duleep Singh, who came to define the image of the Indian royal under British rule. In Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s famous portrait, commissioned by Queen Victoria herself, Duleep Singh is swathed in embroidered silks, crowned by a white turban and sarpech, and dripping in jewels. The queen had very graciously loaned him the family gemstones he had signed over under the Treaty of Lahore as a child of five to Lord Dalhousie. Notably absent, of course, was his father’s beloved Kohinoor, which would be presented to him at the time of the portrait being painted, newly cut and mounted.

This portrait did more than capture a man; it encapsulated an era of orientalist spectacle, framing Indian royalty as both conquered and exotic—ornate tokens of the Empire’s reach. During events like the Delhi Durbars, maharajas were expected to perform this colonial theatre, parading in their courtly finery, their images endlessly reproduced for British audiences. But what began as submission gradually evolved into subtle resistance.

Over time, the same visual codes—silks, jewels, Cartier commissions, French watches, and elaborate tailoring—became tools of reclamation. Stripped of real political power, the princely elite began asserting their cultural sovereignty through style. Their wardrobes became a hybrid performance: a confluence of Indian royal heritage and European cosmopolitanism. The Maharajas of Patiala and Kapurthala were no longer passive muses of the imperial gaze—they became mythmakers, curating their image with strategic flair. In this, too, was a form of dandyism: fashion as resistance, spectacle as authorship, identity styled with intention.

The Met as Durbar

So when Diljit Dosanjh arrived at the 2025 Met Gala in Prabal Gurung’s homage to that legacy, he wasn’t off-theme—he was engaging in a centuries-long visual dialogue. Like the Delhi Durbar of another era, the Met Gala is a carefully choreographed spectacle—an annual ritual of fashion, power, and performance that demands symbolism as much as style.

For his Met Gala debut, Dosanjh wore a cream-white achkan with tone-on-tone embroidery, layered under a dramatic full-length ivory cape. The cape bore a zardozi-embroidered sun and crescent moon on the front, and on the back—a map of Punjab inscribed with the Gurmukhi alphabet. He wore a matching turban and carried a ceremonial kirpan, a visible marker of Sikh identity and sovereignty. His look was completed with custom jewellery by Jaipur-based Golecha’s Jewels. The original plan had included a Cartier necklace once owned by Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, but the request to loan it was denied.

And perhaps that denial is poetic in its own way. Diljit didn’t need the original necklace. His look didn’t rely on historical relics—it was the history. In reclaiming the visual grammar of the maharajas, Dosanjh stages a quiet reversal of the colonial gaze: not a British Empire parading a princely subject, but a Punjabi Sikh artist projecting his own cultural and political inheritance—on his terms, in his voice, on one of the most-watched cultural stages in the world.

Where once maharajas borrowed from the West to perform power, Diljit flips the script—borrowing from their legacy to perform resistance.

The Turban as Theory

Diljit Dosanjh’s appearance at the Met Gala was more than a moment of cultural representation—it was an act of sartorial theory. By donning symbols of Sikh identity and princely heritage, Dosanjh didn’t just wear a look, he authored a statement: that fashion can be archive, ancestry, and argument. In a space where visibility is often commodified, he reclaimed the tools of spectacle—not to flatter the gaze, but to confront it. He stood not as a token, but as a sovereign, wrapped in the language of history and resistance. In doing so, he reminded us that the dandy is never just dressing up. He’s dressing against.

Sabina Gill says:

Very well written article . It made a lot of sense to a layman like me who has no sense of fashion at all

May 11, 2025 — 4:11 am